- Home

- Hilda Eunice Burgos

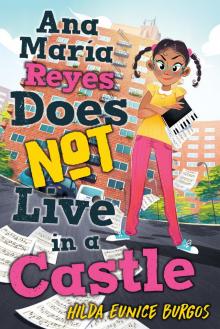

Ana Maria Reyes Does Not Live in a Castle Page 2

Ana Maria Reyes Does Not Live in a Castle Read online

Page 2

“Ay, Anamay, you worry too much. We’ll figure out a way.” She smiled a little. “And remember, we are the Reyes! Wherever we live is our castle.”

Mami’s family’s last name is Castillo, and Papi’s last name is Reyes. In the Dominican Republic, where both my parents were born, when a woman gets married, she keeps her name, adds an “of” in Spanish, or de, and then follows it with her husband’s name. So Mami is a Castillo de Reyes, which means “castle of kings” in Spanish. And that’s how my parents described our home. A castle filled with royalty: our Reyes family.

“Yeah, I know,” I said. “Our castle of kings.”

Mami pulled me toward her for a hug. She didn’t know I was just being polite.

Chapter 2

The next day I went to my piano lesson, as I did every Tuesday after school. My piano teacher, Doña Dulce Sánchez, lived two blocks from my school, in the opposite direction from my house. Her building only had six floors, and the entryway was dark and smelled like dirty wet towels. The elevator broke down a lot, but even when it worked, it was super slow so I didn’t bother waiting for it. Doña Dulce did not like it when a student arrived late.

“I can’t believe that woman’s name is Dulce,” Gracie said before she quit taking lessons. “There’s nothing sweet about her.”

Doña Dulce was definitely tough, and she noticed when you hadn’t practiced. One time she made Gracie play one scale over and over again for her entire lesson. “And that’s how you practice,” Doña Dulce said when the hour was up. Gracie was in tears. She told Mami and Papi that she refused to be mistreated anymore, so they let her quit. I tried to talk her out of it, but she wouldn’t listen to me. Now, after six years of lessons, I could say that, even though she was demanding, Doña Dulce was a really great teacher. In fact, she was probably great because she was demanding. And it’s a wonderful feeling when you finally get a piece right and you hear that beautiful music flowing from your fingers.

As I stood outside the apartment, I could hear Sarita Gómez playing inside. Sarita lived on the sixth floor of Doña Dulce’s building. Her family didn’t have a piano, so she came over every day after school to practice on Doña Dulce’s second piano. It was in the front bedroom, the one that Doña Dulce’s son used to live in before he joined the Marines and moved away.

Doña Dulce’s husband answered the door when I knocked. He stepped to the side so I could squeeze past him into the apartment. I was a little early, so I stopped to listen to Sarita play. Whenever Sarita played I held my breath, because I felt like I’d miss something if I did anything other than just listen. Her playing was so beautiful. Gracie always said Sarita had a special gift, and we couldn’t expect to ever be that good, but I wasn’t going to give up that easily. I admired Sarita’s hard work, and she inspired me to work hard too.

Mr. Sánchez had stopped to listen as well. When Sarita paused, he smiled at me and clicked shut all seven of the locks on the door. “Dulce’s waiting for you,” he said.

I walked down the hallway to the living room. Doña Dulce was not alone. As I came into the room, three people dressed in business suits stood up from the plastic-covered sofa where they had been cramped together — one young woman and two gray-haired men. My teacher shuffled toward me and took my arm. “This is Ana María, one of my best students,” she said.

“Hola, Ana María,” the woman said. “Do you speak English?”

“Of course,” I said. I squinted at her, then remembered that Gracie always said that was my are-you-an-idiot look, so I quickly opened my eyes wide.

“Oh, wonderful!” one of the men said. “My name is Alan Flynn, and these are my colleagues Ms. Alonzo and Mr. Smith. We’re from the Piano Teachers’ Association.”

This was weird. Every year Doña Dulce took her students downtown to be tested by the Piano Teachers’ Association. We each brought a list of about ten pieces we had memorized, and the association judge picked a few for us to play. Doña Dulce said this was how we knew we were really learning, and not just enough to satisfy her. This past year I scored a 92, and Sarita got a 99, even though she probably deserved a 100.

“The testers have been so impressed with the quality of Mrs. Sánchez’s students that we have invited her to bring two performers to our Winter Showcase. Are you familiar with the Winter Showcase?” I shook my head, and Mr. Flynn continued, “We cosponsor it with the Eleanor School, and top piano students from all over the city perform at Lincoln Center.”

The Eleanor School! Would the scholarship people come to the showcase? Could this help me get a full ride?

“So,” Mr. Flynn said, “we will observe your lesson today and later select the two students who will perform.”

“Okay,” I said. I just stood there, not sure what to do next. I couldn’t stop thinking about the possibility of that scholarship.

“Come, come, sit down.” Doña Dulce ushered me onto the piano bench. She took her usual seat in the chair beside me. The plastic on the couch grunted when the three visitors sat back down. “Let’s start with Schumann. ‘The Happy Farmer.’ ”

I was relieved to hear that. When I first learned to play “The Happy Farmer,” I struggled with some of the chords, but not anymore. I started loudly with my left hand, softly with the right. My fingers bounced on the keys, hitting the right notes on tempo, switching the dynamics at the correct moments, ending with a soft, slow chord. By the time I finished, I had forgotten all about the Piano Teachers’ Association people. But then I heard papers rustling and whispered voices, and, right away, I remembered. “Very well executed staccato,” one man murmured. “Great rhythm,” the woman said. I looked at Doña Dulce without turning my head. She was looking at me too. We both smiled.

The rest of the lesson went by quickly. Every time I stopped playing, I heard positive comments from the association people. Then I would sit up a little taller and play a little louder for the next piece. Not to brag, but by the time I played my last piece, I probably sounded like Sarita. Doña Dulce also had me play a few scales and arpeggios to show that I had the basics down.

When my hour was over, I stood up. I wondered if I should just leave or turn around and say goodbye.

“It was very nice to meet you, Ann Marie,” Mr. Flynn said. He held his arm out and shook my hand just like a grown-up.

“Ana María,” I said.

He looked puzzled.

“My name. It’s Ana María, not Ann Marie.”

Mr. Flynn lifted his chin, frowned, and said, “Ohhh.” He looked a little annoyed.

Maybe I shouldn’t have said that, I thought. Maybe I won’t get picked now.

Sarita was in the hallway waiting to come into the living room when I left. We looked at each other and smiled. “You sounded great,” she whispered to me.

“Thanks.” I squeezed past her and headed toward the door. Then I turned around and said, “Good luck, Sarita.” She smiled and gave me a little wave before going into the living room.

Of course she didn’t need any luck. She was definitely going to Lincoln Center. Why did she have to play for them right after me? They would never remember me now.

Chapter 3

I called Claudia as soon as I got home from my lesson. She shrieked when I told her about the Winter Showcase. “This is sooo exciting!” she said. “I’ve seen the showcase, and the kids were really good, just like you!”

I smiled. My friend was so sweet, but was I really as good as those kids? “Do you think this might help me get a scholarship?” I asked.

“Oh, definitely. Eleanor’s head of school always goes to that, and she knows it’s a big deal to be picked to perform. Plus she loves to brag about her students, so she wants kids who do cool stuff like play at Lincoln Center. And then we’ll be at the same school!” She squealed so loudly I had to hold the phone away from my ear. I was excited too, but I had to admit that it didn’t take much to get

Claudia worked up. She even went crazy when I told her about the new baby. “Also, the performers get really dressed up. The girls wear fancy gowns like they’re going to a ball, and the boys wear tuxedos. It’s like playing in a real orchestra or something.”

Hmm, I wasn’t sure about that. I didn’t have any ballroom gowns. But it didn’t make sense to worry about that just yet. I didn’t even know if I was going.

“And then when you get to Eleanor, the music director will beg you to be in the orchestra,” Claudia said. She went on and on about the classes we would take together at Eleanor and the extracurricular activities we would join. She loved to sing, so she was in the choir. “Sometimes the jazz band uses singers, so I’m going to try out for that, and I know they’ll need a piano player, so you should audition too. Oh, I’m so excited!” She shrieked again. I laughed as we said goodbye, then I hung up the phone and went to join Mami and my sisters in the kitchen.

Abuelita had arrived while I was on the phone. She was sitting at the dining table, sideways in her chair, her hands folded over her lap, watching Mami scurry about in the kitchen. Rosie stood on her stool in front of the sink, washing a bowl of lettuce. Gracie sat at the table across from Abuelita. She was embroidering flowers onto a T-shirt for Connie, who sat next to her with a fistful of thread: red, pink, yellow, green, blue, and orange. She handed a pink strand to Gracie.

“Garlic has such a strong smell; it’ll stay on your hands forever,” Abuelita was saying when I walked up to her. I bent down and kissed her cheek. The smell of her perfume made my eyes water a little. Abuelita was even more dressed up than usual, with pearls and a fancy purple dress.

“Bendición, Abuelita,” I said.

“Que Dios te bendiga, mi amor.” Abuelita gave me her blessing. Then she turned back to Mami. “You should wear some rubber gloves, mija.”

Mami nodded as she mashed the garlic in the mortar with a pestle. She scooped the mush out with her bare fingers and lathered it onto the chicken right before she put it in the oven. “How was your lesson?” she asked me.

I told her about the Winter Showcase and how it might help me get a scholarship.

“You know Sarita’s going,” Gracie said without looking up from her embroidery. “But you might get the second spot.”

“Claudia says the performers wear fancy gowns and tuxedos,” I said.

“Oh!” Gracie put the T-shirt down and looked at Mami. “I can make a dress for Anamay to wear to Lincoln Center!”

“What? No, I’m not wearing one of your sewing experiments!”

“Actually, that’s a good idea,” Mami said. “Of course, the material for a fancy dress is harder to work with, so I’ll help. But we can make something much nicer than we could afford from a store.”

“Can’t we buy a regular dress like everybody else?” I said. “If I go, of course.“ I didn’t want to get my hopes up, just in case.

“Don’t worry, Anamay,” Abuelita said. “You know your mother is a wonderful seamstress.”

“Yeah, I know she is.”

Gracie gave me the evil eye. I glared right back at her.

“You must be exhausted, Mecho!” Abuelita said to Mami. “Standing over a hot stove in your condition! Here, let me help you.” She stood up.

“No, Mamá, I’m fine. Anamay will help.”

Ugh, cooking. That was Rosie’s thing, not mine. But I didn’t have any homework, so I could help out. “Sure,” I said. “What do you need?”

Mami handed me some tomatoes and cucumbers and asked me to cut them up to add to the salad. “Rosita, keep an eye on the rice and let me know when the water cooks out.” She sat down next to Abuelita to peel a bunch more garlic for the beans.

“Is Nona staying here with you?” Abuelita asked Mami. Nona was Mami’s younger sister, and she lived in the Dominican Republic. She was coming to visit in a few days.

“No, she’s staying in a hotel.”

“That’s ridiculous! She has family to stay with!”

“I guess she thought everybody would be more comfortable this way.” Mami put the garlic cloves in the mortar and sprinkled salt on them.

“She would be comfortable in my house,” Abuelita said.

Mami gave Abuelita her version of my are-you-an-idiot look. “You live in a studio apartment with just one bed.”

“You and your sisters slept together in one bed your whole childhood. You were comfortable, weren’t you?”

Mami smiled and shook her head. “We’re not children anymore, Mamá.” She pounded the garlic over and over, then looked back up at Abuelita. “Nona says she has a surprise for us.”

“Is it presents?” Connie said.

I kept my eyes on the cucumbers. My aunt had told me about her surprise the last time we spoke, but I had promised to keep it a secret.

“Maybe,” Mami said. She stood up and stirred the mashed garlic into the beans.

Abuelita clasped her hands together. “Maybe Nona’s getting married!” My grandmother always complained about Tía Nona being an “old maid.” “Nona’s going to stay a solterona if she doesn’t apply herself,” she said about once a week.

“Well, she has been talking about Juan Miguel a lot lately,” Mami said.

“He comes from a good family too,” Abuelita said. “He should have good intentions.”

Mami nodded. “It sounds like he makes Nona very happy. But we don’t know if that’s her surprise, so let’s not get too excited.”

Papi walked in the door. “Papi!” Connie and Rosie ran up to him and climbed onto his shoulders.

“I am so hungry.” Papi used his Big Bad Giant voice. “These two little girls look delicious!” Connie and Rosie giggled as he pretended to gobble them up.

“Okay, girls,” Mami said. “It’s time to wash your hands and set the table for dinner. Let’s get an extra chair for Abuelita.”

“Oh, I’m not staying today,” Abuelita said. She stood up, her mouth spreading into a huge smile. “Lalo’s taking me out to dinner for my birthday.”

“Your birthday?” I said. “That was a month ago.” I remembered because Mami had made all of Abuelita’s favorites for dinner and we baked her a cake. Mami’s brother, Tío Lalo, was invited, but he never showed up.

“Well, he’s been very busy.”

“Doing what?” I should have known better than to say anything, but it just came out. By the time I noticed Mami and Papi shaking their heads, it was too late.

“He has a new job! And it’s hard work lifting all those packages in that warehouse, so he gets very tired. But they love him already, so I’m sure he’ll keep this job for a long time!”

“Well, that’s wonderful,” Papi said. “I wish him the best of luck.”

“Are you saying he needs luck? That he’s not smart and hardworking and deserving of a good job?”

“Of course not, Mamá,” Mami said. “It’s just an expression.”

“I know you have no faith in your brother,” Abuelita said. She turned to Papi. “And neither does your husband. And now” — she pointed at me — “now your obnoxious daughter is attacking her own uncle!” She held her head up and marched to the door. “If you can’t respect my son, then I’m not welcome here.” She opened the door and out she went, slamming the door behind her.

We all stood there and looked at the closed door.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I didn’t mean to upset her. I was just asking a question.”

Papi shrugged. “She’ll get over it.”

Mami nodded. “I’ll bring her a plate after we finish eating. She’ll probably be hungry by then.”

Of course we assumed Tío Lalo wouldn’t come through. Again. And Abuelita would be back at our house the next day and she would sit in the dining room, sideways in her chair, her hands folded over her lap, and tell Mami the proper way to fry pl

antains. She wouldn’t even mention her little outburst.

Chapter 4

During dinner we talked about Tía Nona’s visit. “She’ll be here in time for your eighth-grade graduation!” Mami said to Gracie.

“Is Tía Nona bringing me a present?” Connie said. “She didn’t bring me anything last time.”

“You weren’t even born yet last time!” Rosie pressed her forehead into her palm.

“I know. So I didn’t get a present. It’s not fair!”

Mami laughed. “I don’t know if she’s had a chance to buy any presents. She was in Madrid for only a week, and she was working the whole time. The important thing is that we get to see her again. That’s her gift to us.”

“What’s she like?” Connie asked Gracie.

“Oh, she’s beautiful,” Gracie said. “She’s always smiling, and she has dimples, just like you.”

“Really?!”

“Yes, you look a lot like your Tía Nona,” Mami said.

Gracie turned to me. “Do you remember her dimples, Anamay?”

“I remember that she’s really smart,” I said. “She’s the only one in Mami’s family to go to college.”

“That’s right,” Mami said. “She always had her nose in a book when we were kids, just like Anamay.”

“She gave me my first book,” I said. “Since Papi hates to buy books.”

Papi was piling our plates with salad. He stopped and pointed the tongs at me. “Ana María, if we bought you every book you wanted to read, we’d be broke,” he said. Newsflash: We were already broke. “New York City has a wonderful public library system,” Papi continued. “There is no reason whatsoever to waste money on so many books.”

Papi just didn’t get me. But Tía Nona did. Whenever she called Mami, she always spoke with me too. There was so much to tell her about the things I was learning and doing, and she always listened. Plus, she had so many interesting stories to share with me. Her conversations with my sisters were way short. I knew she asked to talk to them just to be polite.

Ana Maria Reyes Does Not Live in a Castle

Ana Maria Reyes Does Not Live in a Castle