- Home

- Hilda Eunice Burgos

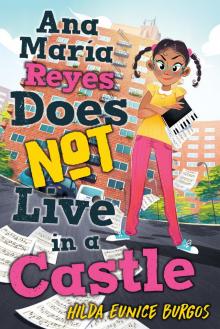

Ana Maria Reyes Does Not Live in a Castle

Ana Maria Reyes Does Not Live in a Castle Read online

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2018 by Hilda Eunice Burgos

Jacket illustration copyright © 2018 by Lissy Marlin

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

TU BOOKS

an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS Inc.

95 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

leeandlow.com

Edited by Cheryl Klein

Book design by Neil Swaab

Typesetting by ElfElm Publishing

Ebook production by Abhi Alwar

The chapter title font is set in Homeward Bound

EPUB ISBN 978-1-62014-363-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Burgos, Hilda Eunice, author.

Title: Ana María Reyes does not live in a castle / Hilda Eunice Burgos.

Description: First edition. | New York : Tu Books, an imprint of Lee & Low Books Inc., [2018] |

Summary: "With a new sibling (her fourth) on the way and a big piano recital on the horizon, Dominican-American Ana María Reyes tries to win a scholarship to a New York City private school" -- Provided by publisher. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2018022776 (print) | LCCN 2018029111 (ebook) | ISBN 9781620143643 (mobi) ISBN 9781620143636 (epub) | ISBN 9781620143629 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: | CYAC: Family life--New York (State)--New York--Fiction. | Dominican Americans--Fiction. | Ability--Fiction. | Scholarships--Fiction. | Bronx (New York, N.Y.)--Fiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.B875 (ebook) | LCC PZ7.1.B875 An 2018 (print) | DDC [Fic]--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018022776

For my parents,

who will always be royalty in my book

Contents

Cast Of Characters

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Acknowledgments

Cast Of Characters

The Reyes Family

Anamay (Ana María): eleven years old

Gracie (Altagracia): Anamay’s thirteen-year-old sister

Rosie (Rosalba): Anamay’s six-year-old sister

Connie (Consuelo): Anamay’s three-year-old sister

Mami (Mercedes “Mecho” Castillo de Reyes): Anamay’s mother

Papi (Gustavo “Tavito” Reyes): Anamay’s father

Friends and Family in New York City

Abuelita: Anamay’s grandmother, Mami’s mother

Tío Lalo: Mami’s brother

Claudia: Anamay’s best friend

Ruben Rivera: Anamay’s friend

Doña Dulce Sánchez: Anamay’s piano teacher

Sarita Gómez: Gracie’s classmate and Doña Dulce’s star piano student

Lucy: Sarita’s sister

Chichi, Lydia, and Millie: Mami’s friends

Pedro, Vicky, and Rebecca: Gracie’s friends

Friends and Family in the Dominican Republic

Tía Nona: Mami’s younger sister

Juan Miguel: Tía Nona’s fiancé/husband

Tía Chea: Mami’s older sister

Tío Pepe: Tía Chea’s husband

Pepito, Juancito, and Muñeca: Tía Chea’s children

Tío Rogelio and Tío Marcos: Papi’s brothers

Clarisa (“Cosita”): Tía Nona’s maid

Chapter 1

Gracie said Mami was right to slap me. She thought I deserved it for what I said. But there were things my sister didn’t know about. Like the conversation I had just had with our parents.

“Look what Mr. Briller gave me!” I told them when I got home from school that day in June. I should have known something fishy was going on because Papi wasn’t at work. But I didn’t ask, because I was glad he was home. He would appreciate the good news I’d gotten from my sixth-grade counselor. “The Eleanor School is offering merit scholarships for the first time in forever, and Mr. Briller thinks I can get one! I just have to take a test in October and fill out this application.” I showed them the packet.

Education means everything to my parents. So the chance to have their daughter go to a top-notch private school for not too much money would be thrilling to them, right? Wrong. They glanced at each other with worried faces. Mami twisted her fingers around like a shy kid about to give an oral report. Papi cleared his throat.

“Ana María,” he said, “that’s a very expensive school. And in eighth grade, you can take the test for Bronx Science.” That was the fancy public high school where a lot of super smart kids in New York City went. Since my neighborhood — Washington Heights — is close to the Bronx, Science was my parents’ dream school for their kids.

“But it’s a scholarship,” I said. “So Eleanor won’t be that expensive. And there’s no guarantee that I’ll get into Science. Gracie didn’t.”

My parents looked at each other again. I knew what they were thinking: Gracie never had a shot at Science because she wasn’t a great student. Unlike me. But they would never say that out loud, because they liked to pretend their four daughters were identical in every way: equally smart, talented, beautiful, sweet, and so on.

“Well . . .” Papi said. “That doesn’t mean anything. I think you definitely have a good chance.”

“But I have a chance at the Eleanor School right now. Don’t you want me to get a good education?”

“Of course we do, mija,” Mami said. “And you’ll get one, just like your sister, even though she's not going to Science.”

My face started to grow warm. “Little Bethlehem High School is nowhere near as good as Eleanor. Not a single member of their graduating class last year went on to an Ivy League school. And look at all that Eleanor has to offer.” I opened the shiny brochure and stood between my parents so they could see the photos of the sprawling green campus, the ginormous science lab with room for all the students to spread out, the happy-looking kids playing brand-new instruments on a polished stag

e.

Papi sighed. “The Eleanor School costs six times more than Little Bethlehem,” he said. “We know that a good education is important to you, and we’re very proud of you, but we just can’t afford a place like that.”

“What if I get a full scholarship?”

My parents’ eyes met again, and they nodded at the same time. “Of course,” Mami said. “We would be thrilled if that happened.”

“But don’t get your hopes up,” Papi said. “After all, we still have to save up for college, and not just for you. We have to think of your sisters too.”

I nodded. Of course I understood. My friend Claudia went to the Eleanor School, and she always talked about how wonderful it was. The caring teachers, the cool field trips, all the different foreign languages offered. Even Latin, which would help with my SATs. But Claudia was an only child. Plus, both her parents made a lot of money. They graduated from Columbia Law School with my dad, which is how they all became friends. But Papi didn’t go on to a fancy law firm like they did. He got his dream job at a place that helps people for free.

“So I can take the scholarship exam, right?” I asked.

“Of course,” Papi said.

“Well,” Mami said to Papi. “Maybe now is a good time for our family meeting.”

Papi nodded. “Ana María, please go get Altagracia, Rosalba, and Consuelo.”

I walked down the hall to the bedroom I shared with Gracie and our six-year-old sister, Rosie. They were on the floor playing with Connie and her dolls. Even though she was only three, Connie could be pretty bossy. “No, no, no!” she was saying to Gracie as I walked in. “You’re the teacher and I’m the mom.”

“Well, who am I?” Rosie looked confused.

“Family meeting, guys,” I said.

Gracie rolled her eyes. Ever since she turned thirteen, that was her favorite thing to do. “Now what?”

I shrugged. The four of us walked down the hall single file.

“Okay, is everyone here?” Papi put his arm around Mami’s shoulder and stood in front of us kids with a big smile on his face.

“We know how much you girls would like to have a brother someday,” Mami said. “And now that just might happen!”

She and Papi giggled, and I started to get a bad feeling in my stomach.

“The new baby will be here in December, near Christmas,” Papi said.

“Oh . . .” Gracie looked at me, and I knew right away she wasn’t happy. “That’s . . . great.”

I could not believe this. I didn’t need my own room or fancy designer clothes. It didn’t bother me that we each got only two gifts at Christmas. And I understood that my parents didn’t always have time to watch me win spelling bees and science fairs. But I really, really wanted — no, needed — a good education. And I might not be able to get one because my parents had too many kids. That was surely why they didn’t want to pay anything for the Eleanor School.

“Where’s the baby gonna sleep?” Connie asked. She wanted to sleep in my parents’ room forever.

“In your crib,” I said. “And you’ll be sleeping on the floor.”

“Ana María, you know that’s not true,” Papi said. “Consuelo, we’ll make sleeping arrangements when the time gets closer.”

“I don’t remember saying I wanted a brother.” Rosie tapped her chin.

“Ay, Rosalba.” Gracie coughed out a fake laugh and rubbed Rosie’s shoulders. “Kids,” she said to Mami and Papi. “They have such poor memories sometimes.”

“There’s nothing wrong with her memory,” I said. Now I was really mad. “None of us wants a brother or another sister. Why do you have to have so many kids anyway? You’re too old to be walking around pregnant. This is embarrassing!”

That’s when Mami slapped me.

***

The moments after the slap felt like they were happening to someone else and I was just watching. I held my hand up to my left cheek. Mami covered her face, burst into tears, and ran down the hall to her bedroom. Gracie gasped. Papi gave me this look, like he was appalled at my very existence, then followed after Mami. Connie scrunched up her face and cried the way she always does whenever she sees tears in someone else’s eyes, and Rosie stroked Connie’s head and told her everything would be okay.

“You deserved that!” Gracie said to me, her nostrils flaring.

“That’s easy for you to say,” I said. “You’ve never been hit before in your life!”

“Duh,” Gracie said. “Neither had you until right now.”

I put my chin in the air. “Well, I guess we’re different now.”

“You’re crazy,” Gracie said. “That’s nothing to be proud of.”

“You’re not happy about this new baby either,” I said. “But you’re too much of a phony to say anything.”

“This has nothing to do with being phony! It’s about being polite and, more importantly, being nice to your mother!” Gracie stomped down the hall and into our bedroom. Rosie and Connie trotted after her. The door shut with a thud, keeping me out.

I stood there and looked at the empty hallway, then I sat on the piano bench with my back to the piano, facing the living room. Had I done something wrong? I was just being honest. And why would Mami want a son anyway? Didn’t she see that might hurt our feelings? Plus, where in the world would this new kid fit? We weren’t a bunch of socks my parents could squish into a drawer. I took off my glasses and rubbed the lenses with the edge of my T-shirt until all the smudges were gone. Then I put my glasses back on and stared at the sharp creases Mami had ironed into my pink cotton pants.

I remembered the first time I walked into this apartment, when I was three years old. I actually thought this place was huge back then. It was still empty, and it seemed as big as a castle. The powder-blue carpet was brand new and springy underneath my feet, and I ran straight through the living room to the wall of windows. From up here on the twelfth floor, the cars looked like toys, and the people would have fit into my hands.

Gracie lay down on the floor of our bedroom and moved her arms and legs back and forth, making snow angels on the pink rug. Mami and Papi took me to their bedroom, which had a door leading to a cement terrace with a high iron fence all around it. We went out to the terrace and Mami held my hand tightly. When I took a step toward the fence, she pulled me back. “I don’t want you to fall over,” she said. Then she showed me the bathroom, full of room to move around. I thought we lived in a mansion.

I was wrong. Now we can’t look out the windows because of Mami’s jungle of plants. The bathroom is stuffed with hair products, magazines, and laundry hampers, and my sisters and I are so crammed into our tiny bedroom, there isn’t even room for a bookshelf. And my parents wanted to squeeze another person in here? I was getting angry again. I got up and opened the piano bench. Practicing would calm me down. It always did.

As I sat back down I accidentally knocked over one of the photos on top of the piano. It was the one of Papi’s mother, who I never got a chance to meet before she died three years ago. Papi used to go to the Dominican Republic to visit her every year. I remembered one time, when I was five, he brought home some guava-and-milk candy packed among his clothes. The wrapping must have come loose, because when he opened the suitcase, ants swarmed all around. Mami and Papi quickly dragged the suitcase into the bathtub. Mami grabbed all the clothes and took them to the laundry room in the basement. Papi threw the food out in the trash chute in the hallway outside our apartment. And they scrubbed the suitcase clean. But I still couldn’t get those ants out of my mind. I woke Mami up three times in the middle of the night because I felt like ants were crawling all over my body. First she scrubbed me down with a washcloth and helped me put on different pajamas. Then she changed my sheets. Finally she took me into her bed and let me sleep with her. All for imaginary insects.

“I guess Mami’s not so bad,” I sai

d to my grandmother’s picture. “And I definitely shouldn’t have called her old. Old people hate that.” I put the photo down and headed toward my parents’ bedroom. I was a little nervous about apologizing to Mami. She always forgave us no matter what we did, but she also never got upset enough to hit us. So she was obviously super mad today. I lifted my hand to her closed door and took a deep breath before knocking.

Papi opened the door and nodded when he saw me. Then he left the room so I could be alone with Mami. She was sitting on the edge of the bed, still sniffling a little.

“I’m sorry, Mami,” I said. She looked so sad and I felt like an awful person for hurting her feelings. “You’re not old, and you’re not embarrassing. I’m proud that you’re my mother.” I really meant that, but I didn’t know if she would believe me.

Mami patted the bed beside her. “Come, sit down.” She stroked the hair above my ear, then curled the bottom of my braid with her finger. “Anamay, I’m so sorry I hit you. I shouldn’t have lost my temper like that.”

“That’s okay,” I said. “It didn’t really hurt that much.” Which was actually true.

“You know your father and I will always love you and your sisters very much. That’s the great thing about a family. Love is multiplied when there are more people, not divided.”

I stared at my fingernails.

“You do know that, right?” Mami said.

I nodded. I did not look up. Math was my best subject at school, and Mami’s calculations didn’t sound right to me.

Mami waited a little bit before she spoke again. “Tell me what’s bothering you.”

I shrugged. My glasses were sliding down my nose, so I pushed them back up with one finger. Mami was still waiting. She wasn’t going to leave me alone until I said something. But I couldn’t tell her the truth. If I said I didn’t think she loved me as much as my sisters, and that a new baby would make that even worse, she might admit I was right. And I didn’t want to hear that. “I just really want to go to the Eleanor School,” I said. “Plus, this place is so small. When Connie grows out of the crib, there’ll be four of us in one room. And where will this last kid fit?”

Ana Maria Reyes Does Not Live in a Castle

Ana Maria Reyes Does Not Live in a Castle